September 4, 2025

Seismic risk prevention: legal obligations and retrofit solutions for companies

Is seismic risk assessment a legal obligation? The answer can only be yes.

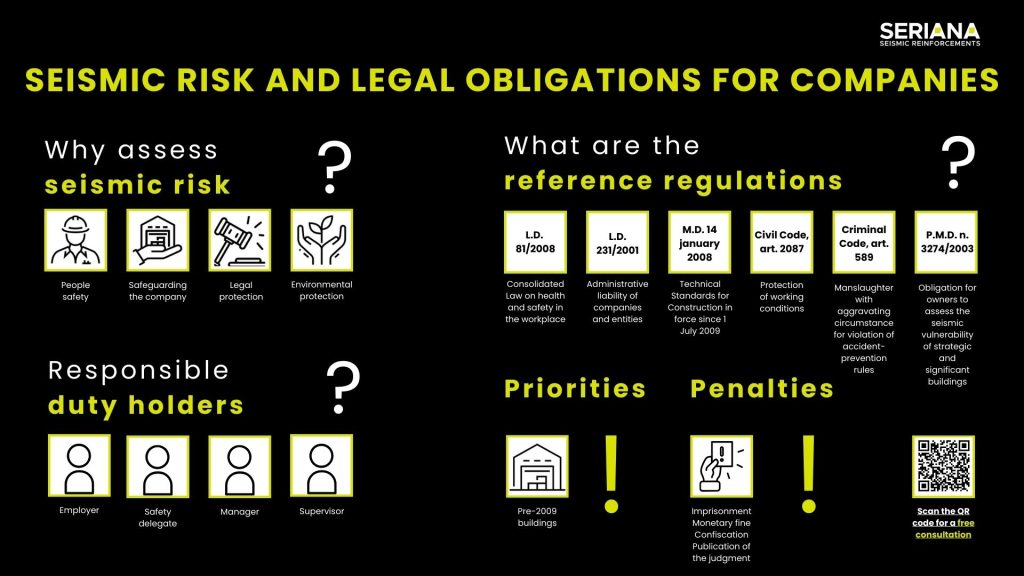

Preventing seismic risk is not only good practice: it is a legal duty and a responsibility toward workers, company assets, business continuity and the environment. Italian regulations are explicit: seismic risk must be assessed and managed in the DVR – Risk Assessment Document (Legislative Decree 81/2008); it must be framed within organizational models and management systems (Legislative Decree 231/2001); and it falls under the responsibility of the employer or the appointed safety delegate to adopt all safety measures (Art. 2087 of the Civil Code), with possible criminal implications in case of omissions (Art. 589 of the Criminal Code). For strategic and relevant buildings, a seismic vulnerability check is required (O.P.C.M. 3274/2003). In short, prevention is a legal obligation even before being a moral one.

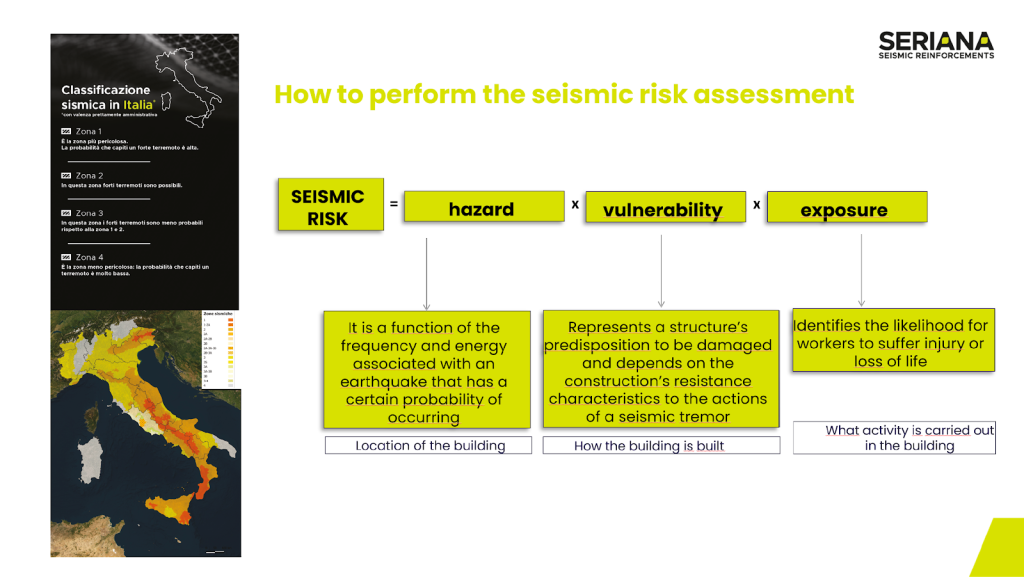

Before getting into individual legislative references, two operational points are worth fixing: seismic risk must be included in the company risk assessment and, by its nature, constitutes a material risk for workers, because it can cause significant harm with a non-negligible probability. Consequently, seismic safety assessment is not optional.

Which buildings must be checked (and often improved/retrofitted)? All those not designed in accordance with the Ministerial Decree 14/01/2008 (NTC 2008), the standards that came into force on 1 July 2009. For these buildings it is necessary to schedule a seismic safety assessment and, if required, an anti-seismic intervention (improvement or upgrading) to protect people, the environment and business continuity.

I. Legislative Decree 81/2008, as amended

What does Legislative Decree 81/2008 provide? – Risk Assessment Document (DVR) and the duty to assess seismic risk

The employer must assess all risks, none excluded, including earthquakes, as set out in Art. 15 – “General protective measures”.

“The general measures for the protection of workers’ health and safety in the workplace are:

a) the assessment of all risks to health and safety;

b) the planning of prevention, aimed at an overall approach that consistently integrates, within prevention, the company’s technical-production conditions as well as the influence of environmental factors and work organization (…);

c) the elimination of risks and, where this is not possible, their reduction to a minimum in relation to the knowledge acquired on the basis of technical progress.”

Article 17 – Non-delegable obligations of the employer

“1. The employer may not delegate the following activities:

a) the assessment of all risks, with the consequent preparation of the document provided for in Article 28;

b) (…)”

Article 28 – Object of the risk assessment

“1. The assessment referred to in Article 17, paragraph 1, letter a), including in the choice of work equipment and of the substances or chemical preparations used, as well as in the layout of workplaces, must cover all risks to the safety and health of workers (…).”

In conclusion, Legislative Decree 81/2008 establishes that the assessment of all risks—including seismic risk—and the drafting/updating of the DVR are non-delegable obligations of the employer. This assessment must encompass equipment, substances used, and the organization/layout of workplaces, so as to ensure effective protection of workers’ health and safety and to avoid liabilities and sanctions.

What are the requirements for workplaces?

Article 63 – Health and safety requirements

“Workplaces must comply with the requirements set out in ANNEX IV (…).”

Article 64 – Employer’s obligations

“It is mandatory that systems and safety devices intended to prevent or eliminate hazards are subjected to regular maintenance and functional checks.”

Annex IV – Workplace environment requirements

“1.1. Stability and robustness

1.1.1. Buildings housing workplaces, or any other works and structures present in the workplace, must be stable and have a robustness consistent with their intended use and with environmental conditions (…).”

In summary, Articles 63 and 64 of Legislative Decree 81/2008, together with Annex IV, require that workplace buildings and structures be stable and suitable for their use and environmental conditions (including earthquakes). The employer must regularly maintain and check systems and safety devices, taking action whenever issues arise.

From assessment to operational decisions

The seismic risk assessment must be entrusted to a qualified professional and takes the form of a Safety Assessment of the building. Operational decisions follow from this: when performance is adequate, no works are required; if shortcomings emerge, seismic retrofit or improvement measures are planned; where minimum safety levels cannot be ensured, usage limitations or downgrading of areas are applied.

Particular attention must be paid to prefabricated industrial buildings not designed with seismic criteria: damage experience and technical literature highlight recurring weaknesses in beam–column, roof–beam, and cladding panel–column connections, as well as in the bracing of storage racks. These are clear weak points that cannot be ignored during verification.

Finally, it is essential to dispel a common misconception: certificates of occupancy, commissioning tests and other administrative permits do not equate to a seismic safety standard. For workplaces, it is necessary to verify that the buildings housing production activities have been constructed (or retrofitted) with features suitable to ensure stability and resistance in the event of an earthquake. Only then does seismic prevention become concrete, measurable, and consistent with legal obligations.

The specific case of prefabricated industrial buildings: Article 29 – Methods of conducting the risk assessment ( … )

“Risk assessment must be immediately revised, in accordance with the procedures set out in paragraphs 1 and 2, in the event of changes to the production process or to work organisation that are significant for workers’ health and safety, or in relation to the state of the art in technology, prevention or protection ( … ). Following such revision, prevention measures must be updated ( … ).”

What must the employer do once critical issues have been identified? Article 64 – Employer’s obligations

“1. The employer shall ensure that:

( … )

c) workplaces, systems and devices are subjected to regular technical maintenance and that any defects identified which may jeopardise workers’ health and safety are remedied as quickly as possible;

( … )”

II. Beyond D.Lgs. 81/2008: what ASL, the Ministry of Labour and Civil Protection say

Alongside the general obligations of the Consolidated Safety Act, several official notices have clarified that seismic risk must be explicitly assessed in the DVR and, where necessary, followed by seismic retrofitting or upgrading works.

The Bergamo ASL, in a letter from the Directorate-General dated 1 April 2014 (subject: “Assessment of seismic risk in prefabricated industrial buildings not designed with anti-seismic criteria”), reminded employers—pursuant to Arts. 17 and 28 of D.Lgs. 81/08—of the obligation to carry out a specific earthquake-risk assessment, stressing the high vulnerability of these structures, particularly if built before seismic zoning.

The same line is reiterated by the Ministry of Labour in a press release (Rome, 6 June 2012): the stability and solidity of buildings are safety requirements referred to in Annex IV of D.Lgs. 81/2008; failure to comply is punishable and cannot be “neutralised” by waivers. The standardised procedures for risk assessment also include natural events—earthquakes among them—among the hazards to be considered, in line with the DVR’s required “global” approach.

Finally, OPCM 3274/2003 introduced an obligation on owners to verify the seismic vulnerability of buildings whose functionality is strategic or whose potential failure could have significant consequences; this applies both to existing buildings whose functionality during seismic events is fundamental for Civil Protection purposes and to buildings that may become relevant in relation to the consequences of a possible collapse.

In practice: for many production sites—particularly for “legacy” prefab buildings—a generic assessment is no longer sufficient; a targeted seismic diagnosis is needed and, where required, a seismic-retrofit programme that protects people, the environment and business continuity.

III. CIVIL CODE – Art. 2087 (Protection of working conditions)

“Entrepreneurs are required, in the conduct of the undertaking, to adopt the measures which, according to the particular nature of the work, experience and the state of the art, are necessary to protect the physical integrity and moral personality of workers.”

In other words, the employer must ensure a safe working environment, adopting—based on the nature of the activity, experience and current best practice—all measures suitable to safeguard workers’ health and dignity. It is an “open-ended” clause: it requires risks to be prevented even beyond the bare legal minimum whenever necessary.

IV. CRIMINAL CODE – Art. 589 (Manslaughter) and paragraph repealed by Law 23 March 2016, No. 41

“Anyone who, through negligence, causes the death of a person shall be punished with imprisonment from six months to five years. If the act is committed in breach of the rules on the prevention of workplace accidents, the penalty shall be imprisonment from two to seven years (…)”

“In the case of the death of several persons, or the death of one or more persons and injury to one or more persons, the penalty applicable for the most serious of the violations committed shall be increased up to threefold, but the penalty may not exceed fifteen years.”

In conclusion, anyone who negligently causes another’s death is punishable by 6 months to 5 years’ imprisonment. If the event occurs in breach of occupational safety rules, the penalty rises to 2–7 years. Where there are multiple fatalities (or fatalities and injuries together), the penalty for the most serious violation may be increased up to three times, with an overall cap of 15 years.

V. Legislative Decree 8 June 2001, No. 231 – “Administrative liability of companies and entities” and subsequent amendments by Law No. 179 of 30 November 2017

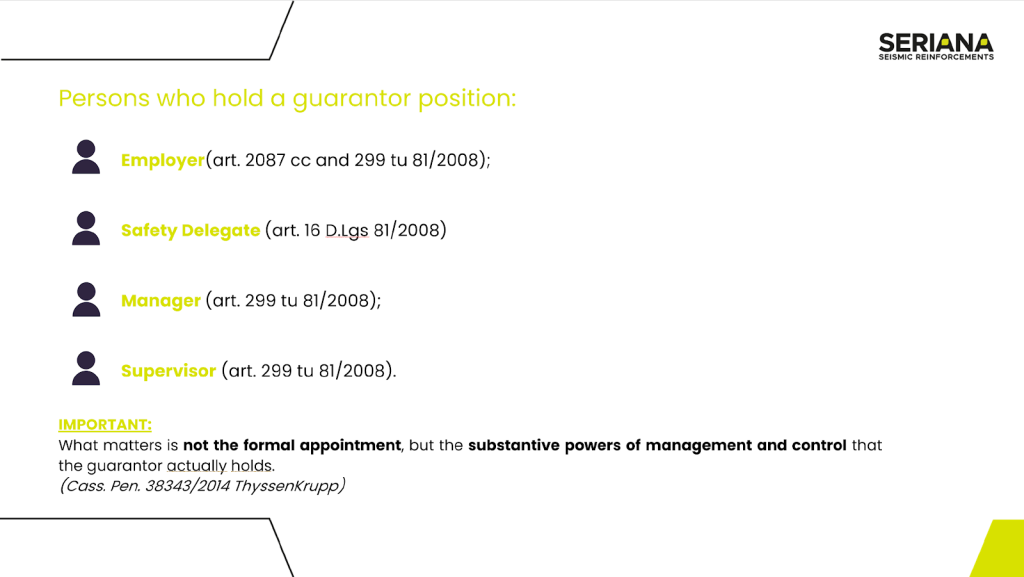

D.Lgs. 231/2001 introduces the administrative liability of legal persons (companies and entities) for offences committed by their representatives, directors, employees or third parties acting in their name and on their behalf.

Law 179/2017, which amends the decree, strengthens the sanctions regime and requires the adoption of effective Organisation, Management and Control Models (MOG) to prevent offences.

In particular, Articles 5 and 6 highlight the liability of those who hold functions of representation, administration or management within the company. If such a person (e.g., CEO, country manager, or similar) fails to fulfil their duties—such as compliance with safety rules or environmental risk requirements—the company may seek recourse against that individual. This creates significant exposure for managers, especially in the event of workplace accidents or seismic events.

Each role is crucial in ensuring that the company complies with laws on safety, prevention and protection, particularly in critical situations such as workplace accidents or earthquakes.

What conditions trigger a company’s liability for the offence of negligent injury/manslaughter of a worker?

The offence was committed in the interest or to the advantage of the entity;

No adequate Organisation, Management and Control Model (MOG) was adopted;

No Supervisory Body (OdV) was appointed.

What are the sanctions?

- Monetary fine up to approx. €1,500,000;

- Disqualifying measures from 3 to 12 months;

- Confiscation;

- Publication of the judgment.

Are D.Lgs. 231/2001 and D.Lgs. 81/2008 connected?

Legislative Decree No. 231/2001 has been extended to negligent offences in the field of workplace safety, including manslaughter and serious personal injury, pursuant to Art. 9 of Law No. 123/2007.

This made it necessary for companies, including smaller ones, to adopt an Organisation, Management and Control Model (MOG) to prevent such offences.

In particular, Art. 6 of Decree 231 provides that, to exclude the entity’s liability, the latter must adopt an effective MOG.

D.Lgs. 81/2008 requires the adoption of a Safety Organisation and Management Model (MOGS) which, if properly implemented, exempts the entity from the sanctions provided by Decree 231.

The two models (MOG and MOGS) are distinct but coordinated, with the Supervisory Body (OdV) overseeing their implementation, ensuring workplace safety and preventing the risk of offences. In addition, Art. 30 of D.Lgs. 81/2008 and Art. 6 of D.Lgs. 231/2001 stress that adopting a MOG entails further obligations, such as risk assessment and safety measures.

In short, a MOG cannot be considered “effectively implemented” unless all the obligations under D.Lgs. 81/2008 are also fulfilled, including the Risk Assessment Document (DVR) and the related prevention measures.

Conclusion

In Italy, seismic risk in workplaces is governed by a set of provisions that converge on key pillars: assessing all risks (earthquakes included), ensuring building stability and robustness, keeping systems and safety devices efficient, planning works and maintenance, and organising emergency management. In practice, compliance requires a technical-structural diagnosis, the definition of priorities and timelines for action (seismic retrofit or upgrade), document traceability, and the active involvement of the employer/plant operator. It is a continuous improvement journey in which seismic retrofit turns legal obligations into tangible safety for people, company assets, business continuity, and the environment.